It has been a while since my last On Coding installment — I talked about Mathematica and functional programming. Now its time to talk about one of my favorite programming languages: Postscript!

Chronologically, we’re back in my undergraduate days, around sophomore year. Recall that means no laptops, no slick user interfaces, no real windows environments like we know today. This meant if you wanted to play around wtih computer graphics, you had to go to a computer lab and write code. Postscript was the language of choice.

And get this. The only way to see if you wrote your code correctly was to print out your graphics. No fancy clicking your mouse and having the image rendered on your screen. This meant debugging wasn’t so easy….

Two important features of Postscript are that it’s a stack-based language, and the notation is postfix — meaning the arguments come before the function call. Just like my HP-15C programmable calculator, which is still functioning perfectly despite being over thirty years old. It’s my go-to calculator when I want to make quick calculations.

I won’t go into detail here, since I discussed these two features at length in my Day037 blog post, Fractals VIII: PostScript Programming. Feel free to go back and refresh your memory if you need to….

What I will discuss today are the two primary things I use Postscript for now: iterated function systems and L-systems.

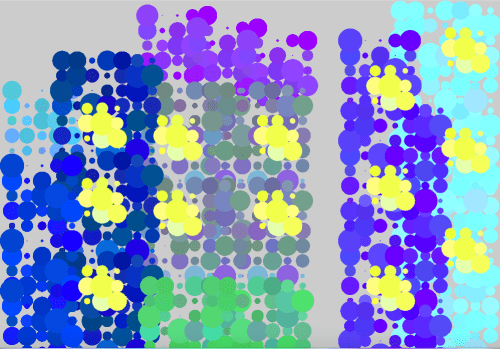

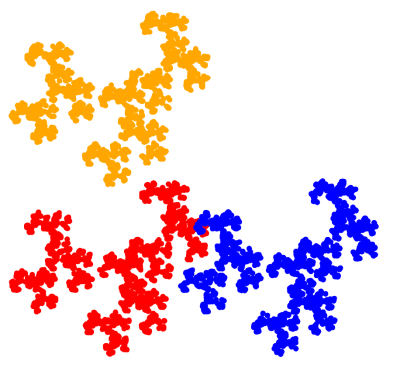

OK, I won’t really discuss iterated function systems as far as the algorithm is concerned…I’ve talked a lot about that before. But what’s significant is that’s when I started getting hooked on fractals. I had read about IFS in a paper by Michael Barnsley (before his famous Fractals Everywhere was written) just a few years after Mandelbrot’s The Fractal Geometry of Nature was first published. Fractals weren’t so well-known at the time, but they were making quite a buzz in the mathematical community.

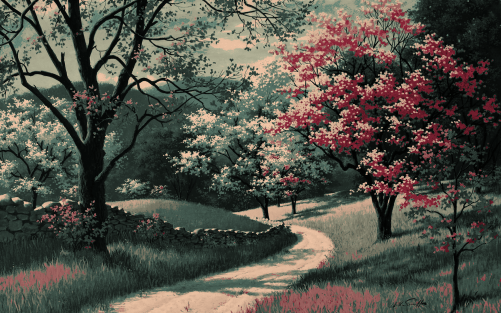

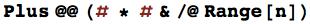

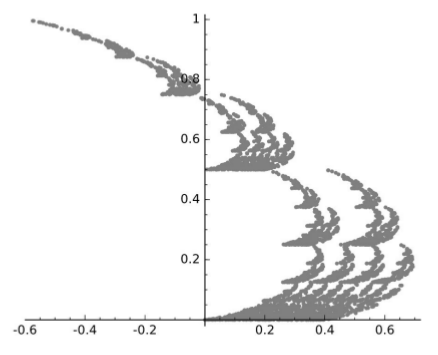

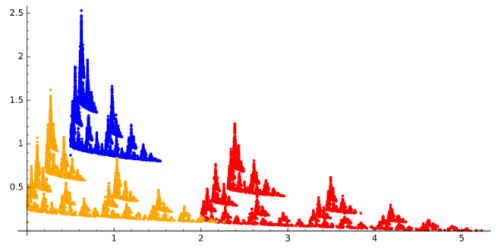

What was really neat was that I could make my own fractals in Postscript. I was really struck by the wide variety of images you could make with just two affine transformations. My favorite is still The Beetle.

Now this particular image didn’t get rendered in Postscript until much later (my files are dated 1998), but the seeds were well-planted. And fortunately, by then, there were nice GUIs so I didn’t have to rely on printing each image to see what it looked like…. I still use my old Postscript code to teach IFS occasionally, as I did with Thomas.

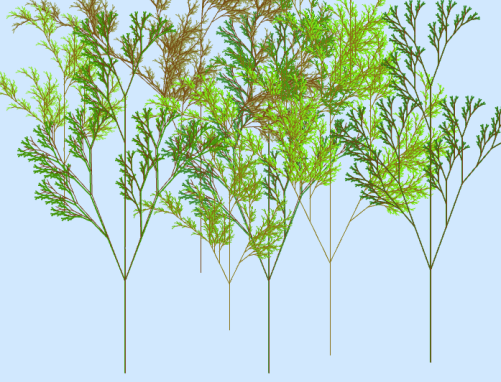

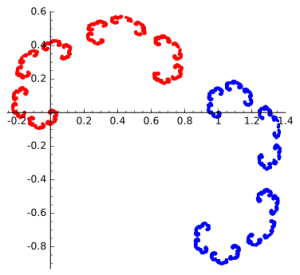

The other significant use of Postscript is in modeling L-systems (I’ve talked about these before, here is a nice Wikipedia page on the subject). In particular, I implemented basic turtle graphics routines so I could imitate many of the well-known algorithms for creating fractals like the Koch and dragon curves.

Of course these algorithms could be implemented in any programming language. But I didn’t have access to Mathematica at the time, I loved Postscript, and it was open source. So it was a natural choice for me.

For the graphics programmer, there are a few particularly useful functions in Postscript, gsave and grestore. These functions save and restore (respectively) what is called the graphics state. In other words, if you are creating a graphical object, and would like to create another and return where you left off, you would invoke gsave, go do your other bit, and then use grestore to return where you left off. Like a stack for graphics.

What this does is save all the parameters which influence how graphics are drawn — the current origin, rotation of axes, line thickness, color, dash pattern for lines, etc. And there are a lot of such parameters possible in Postscript.

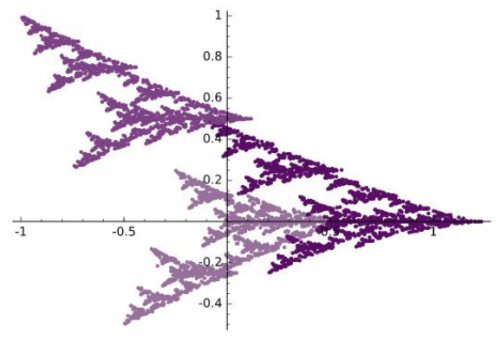

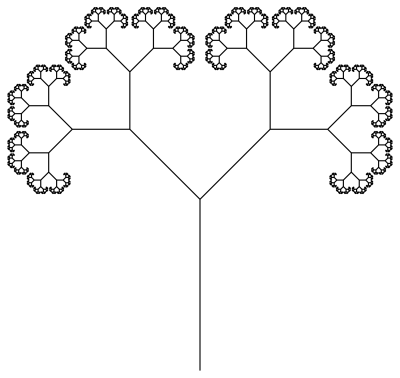

And while you might not think this is a really interesting feature, it’s great for working with L-systems, especially bracketed L-systems. You might recall that a very basic binary tree is represented by the bracketed L-system

Basically, this means that a tree T is drawn first by moving forward some length s. Remember where you are (“[“), then, turn left some given angle, and then draw a tree whose beginning segment has length rs, where r is less than 1, so that the left branch is a self-similar version of the whole tree. Finish that tree (“]”), and go back to where you were. Then repeat on the right-hand side. Here is a simple example with a branching angle of 45 degrees, and a branching ratio of 0.58.

You might have guessed the punch line by now: use gsave for “[” and grestore for “].” Really nice! There are a few other subtleties to take care of, like remembering the depth as you go along, but the gsave and grestore functions essentially make implementing bracketed L-systems fairly easy in Postscript.

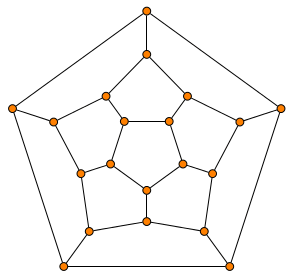

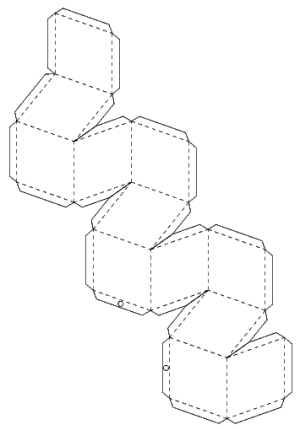

While I now use Postscript primarily for IFS and L-systems today, I’ve had other adventures with Postscript over the years. Before they were easily available online in other places, I used Postscript to create dozens of nets for making polyhedra, such as the net for the rhombic dodecahedron shown below.

I had taught a course on polyhedra and geodesic structures for many years, so it was convenient to be able to make nets for classroom use.

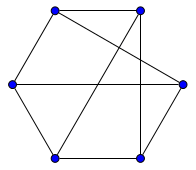

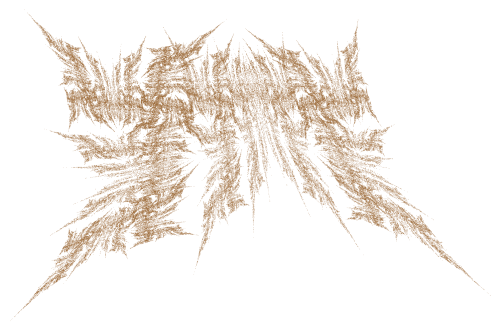

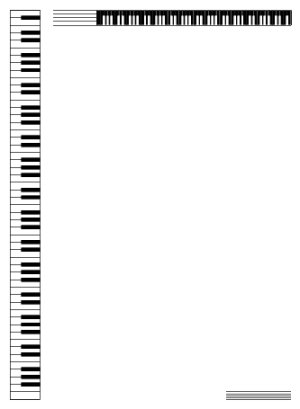

I also played with designing fonts for a while (though I think those files are gone forever), and enjoyed designing stationery as well. Here was one of my favorites.

I just printed this motif on some nice paper, and used it to write letters — back in the day when people actually wrote letters! It was fun experimenting with graphic design.

True, not many people program in Postscript now, since there are so many other options for producing graphics. But I do always encourage students to dabble for a bit if they can. Programming in Postscript gets you thinking in postfix and also thinking about stacks. And while you may not use these concepts every day when programming, it’s good to have them in your coding arsenal. Gives you more options.

In the next installment, I’ll talk about markup languages — and HTML. Until then!