Today, we’re going to wrap up our discussion of iterated function systems by looking at an algorithm which may be used to generate fractal images.

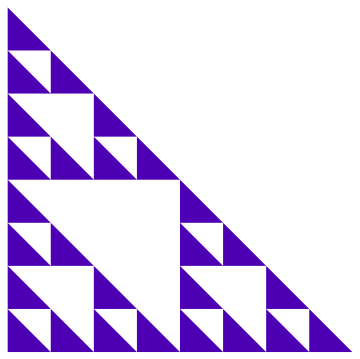

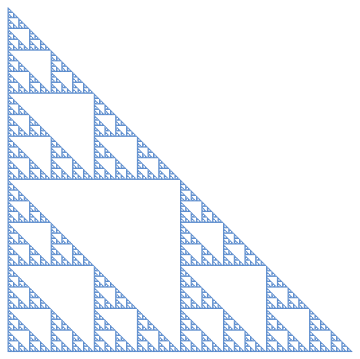

Recall (look back at the first post if you need to!) the Sierpinski triangle. No matter what initial shape we started with, the iterations of the function system eventually looked like the Sierpinski triangle.

But there’s a computational issue at play. Since there are three different transformations, each iteration produces three times the number of objects. So if we carried out 10 iterations, we’d have 310 = 59,049 objects to keep track of. Not too difficult for a computer.

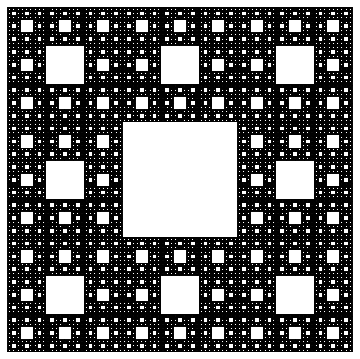

But let’s look at the Sierpinski carpet. With eight different transformations, we’d have 810 = 1,073,741,824 objects to keep track of. Keeping track of a billion objects just isn’t practical.

Of course you could use fewer iterations — but it turns out there’s a nice way out of this predicament. We can approximate the fractal using a random algorithm in the following way.

Begin with a single point (usually (0,0) is the easiest). Then randomly choose a function in the system, and apply it to this point. Then iterate: keep randomly choosing a function from the system, then apply it to the last computed point.

What the theory says (again, read the Barnsley book for all the proofs!) is that these points keep getting closer and closer to the fractal image determined by the system. Maybe the first few are a little off — but if we just get rid of the first 10 or 100, say, and plot the rest of the points, we can get a good approximation to the fractal image.

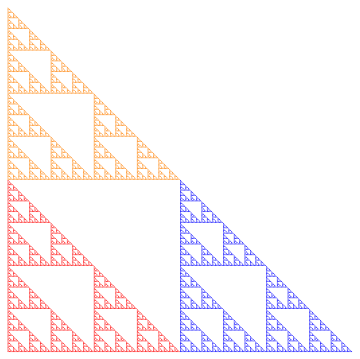

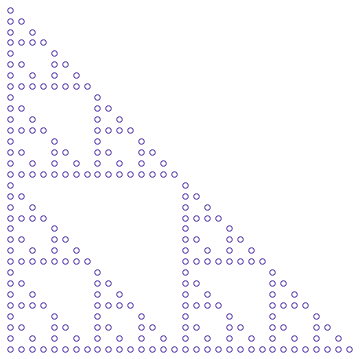

Consider the Sierpinski triangle again. Below is what the first 20 points look like (after (0,0)), numbered in the order in which they’re produced.

Let’s look at this in a bit more detail. For reference, we’ll copy the function system which produces the Sierpinski triangle from the first post.

Now here’s how the color scheme works. Any time is randomly chosen, the point is colored red. For example, you can see that after Point 6 was drawn,

was chosen, so Point 7 was simply halfway between Point 6 and the origin.

Any time is chosen, the point is colored blue. For example, after Point 8 was drawn,

was randomly chosen. You can see that if you move Point 8 halfway to the origin and then over right one unit, you land up exactly at Point 9.

Finally, any time is chosen, the point is colored orange. So for example, it should be clear that moving Point 7 halfway toward the origin and then up one unit results in Point 8.

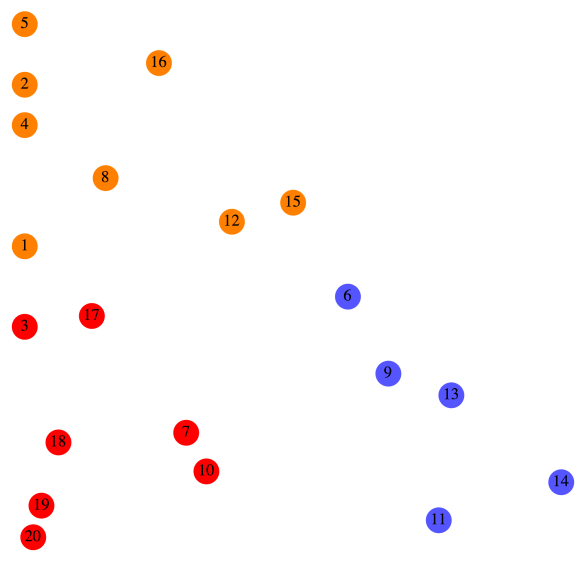

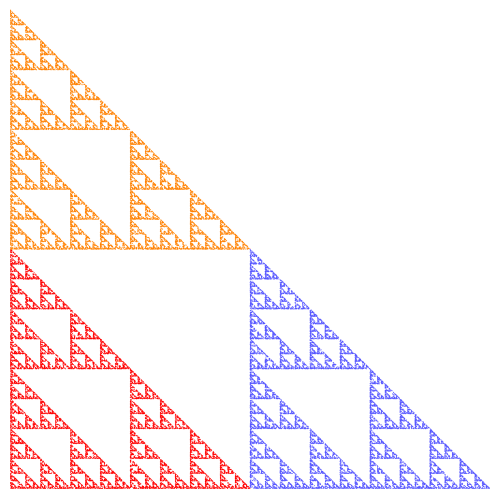

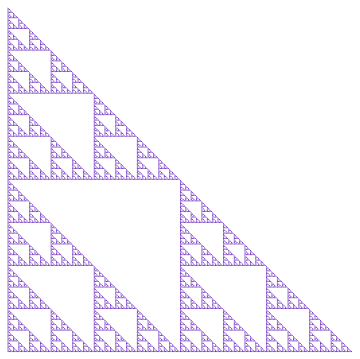

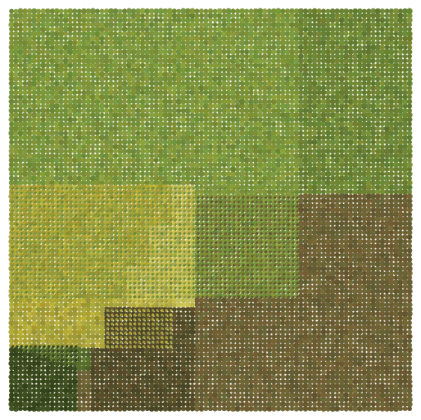

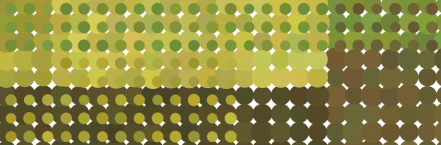

Of course plotting more points results in a more accurate representation of the fractal. Below is an image produced using 5000 points.

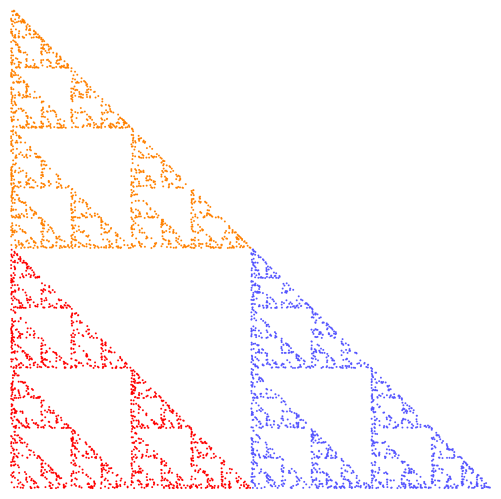

To get more accuracy, simply increase the number of points, but decrease the size of the points (so they don’t overlap). The following image is the result of increasing the number of points to 50,000, but using points of half the radius.

There’s just one more consideration, and then we can move on to the Python code for the algorithm. How do we randomly choose the next affine transformation?

Of course we use a random number generator to select a transformation. In the case of the Sierpinski triangle, each of the three transformations had the same likelihood of being selected.

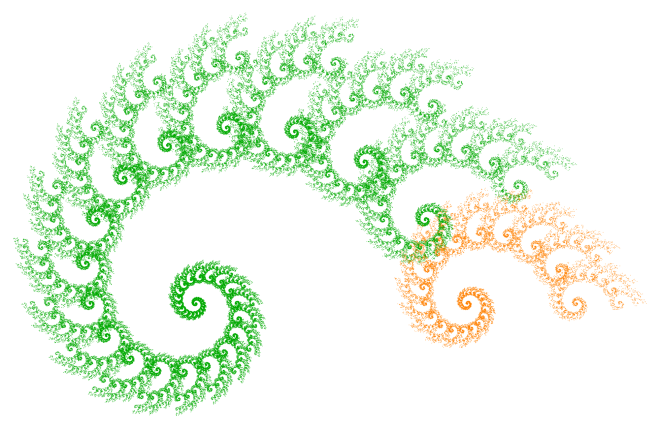

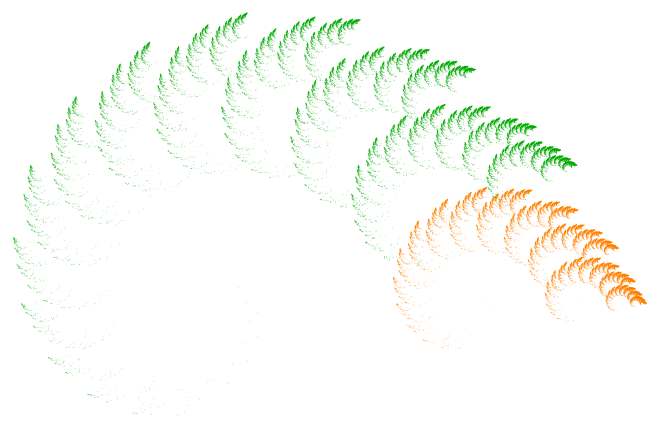

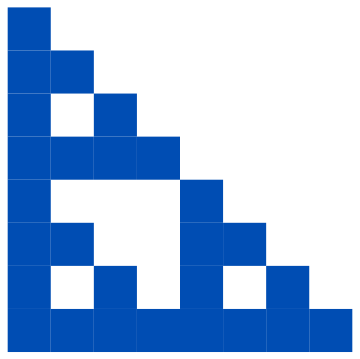

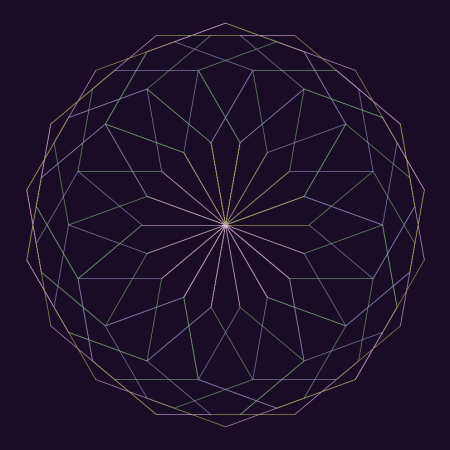

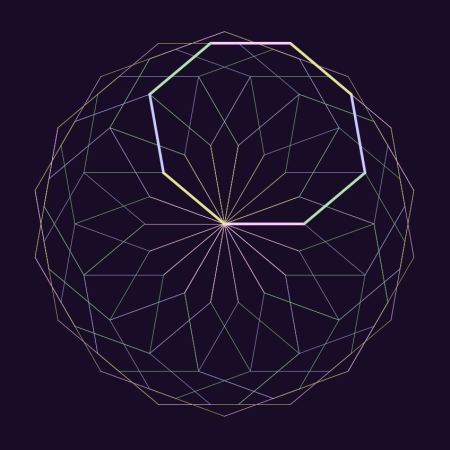

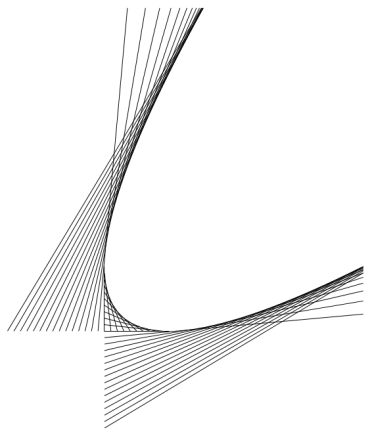

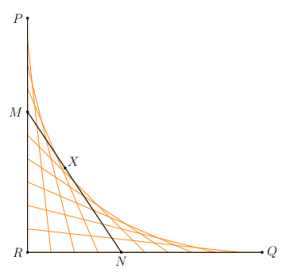

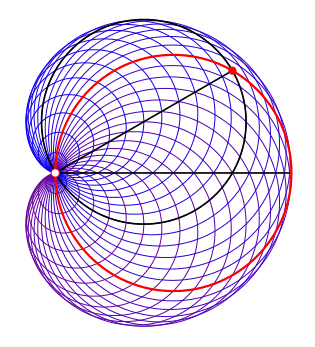

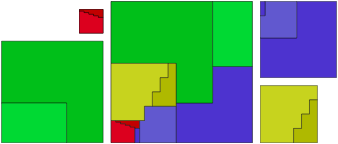

Now consider one of the fractals we looked at last week.

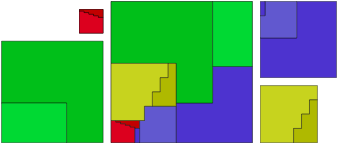

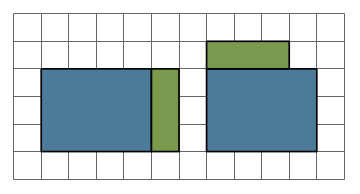

If the algorithm chose either transformation with equal probability, this is what our image would look like:

Of course there’s a huge difference! What’s happening is that transformation

Of course there’s a huge difference! What’s happening is that transformation actually corresponds to a much smaller portion of the fractal than

— and so to get a more realistic idea of what the fractal is really like, we need to choose it less often. Otherwise, we overemphasize those parts of the fractal corresponding to the effect of

Again, according to the theory, it’s best to choose probabilities roughly in proportion to the portions of the fractal corresponding to the affine transformations. So rather than a 50/50 split, I chose 87.5% of the time, and

just 12.5% of the time. As you’ll see when you experiment, a few percentage points may really impact the appearance of a fractal image.

From a theoretical perspective, it actually doesn’t matter what the probabilities are — if you let the number of points you draw go to infinity, you’ll always get the same fractal image! But of course we are limited to a finite number of points, and so the probabilities do in fact strongly influence the final appearance of the image.

So once you’ve chosen some transformations, that’s just the beginning. You’ve got to decide on a color scheme, the number of points and their size, as well as the probabilities that each transformation is chosen. All these choices impact the result.

Now it’s your turn! Here is the Sage link to the python code which you can use to generate your own fractal images. (Remember, you’ve got to copy it into one of your own Projects first.) Freely experiment — I’ve also added examples of non-affine transformations, as well as affine transformations in three dimensions!

And please comment with interesting images you create. I’m interested to see what you can come up with!

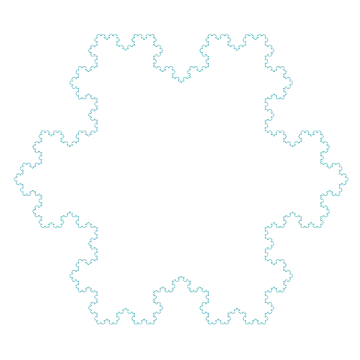

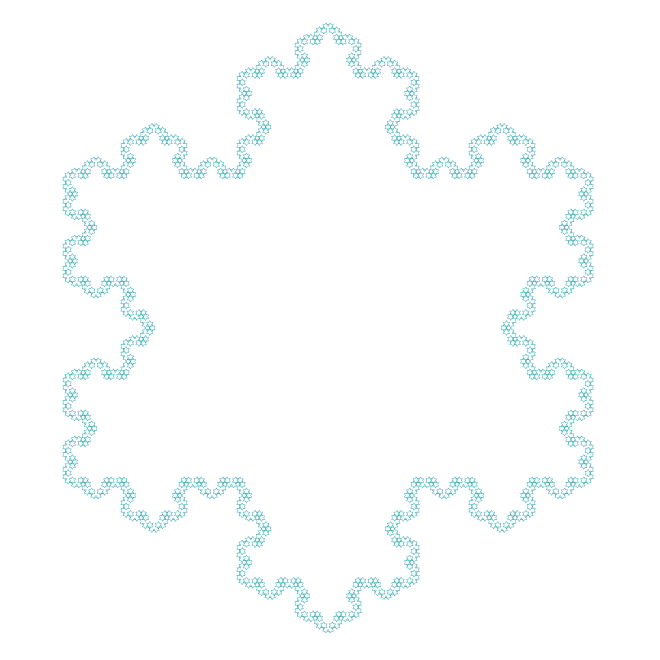

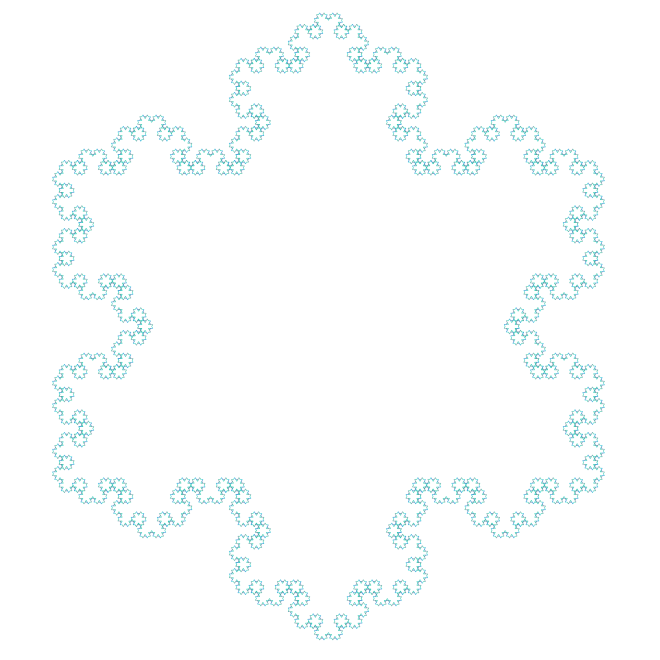

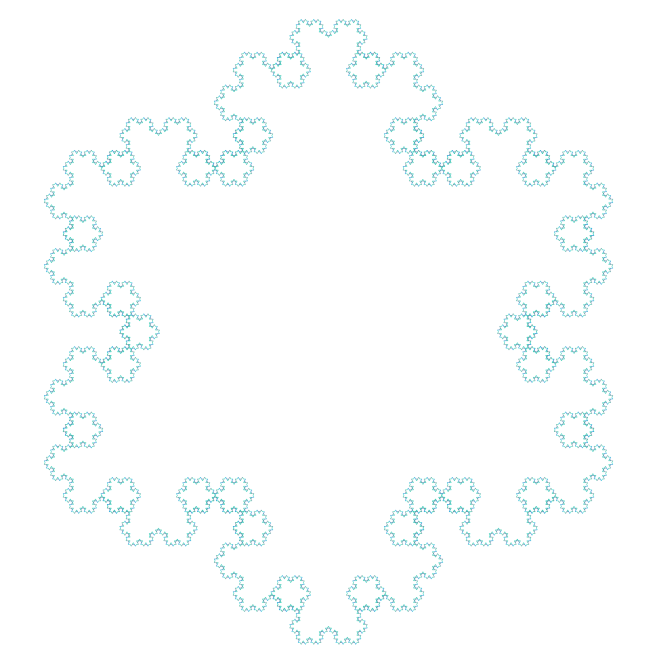

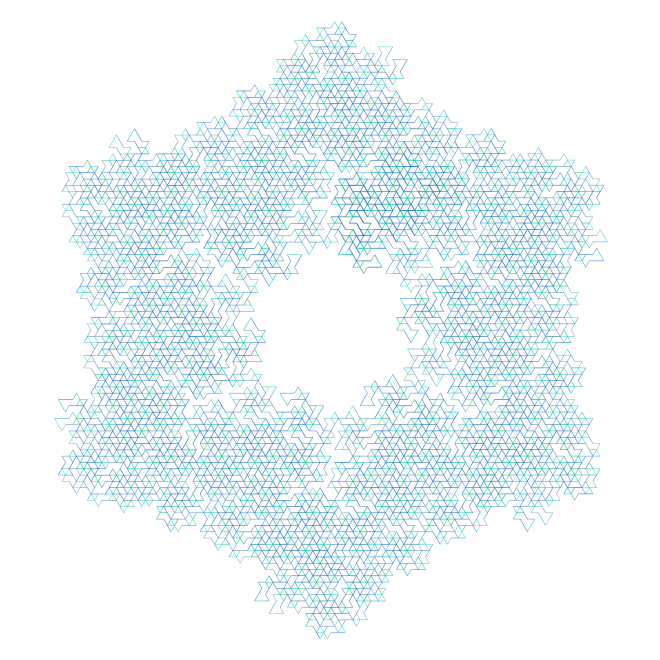

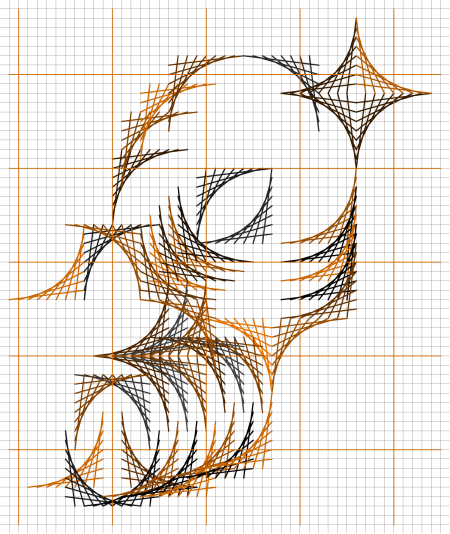

There’s so much you can do with just one pair of transformations!

There’s so much you can do with just one pair of transformations!

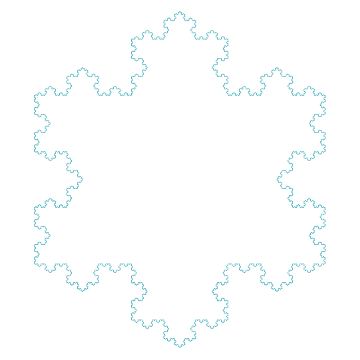

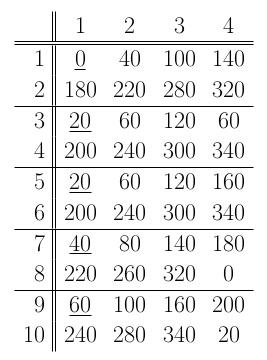

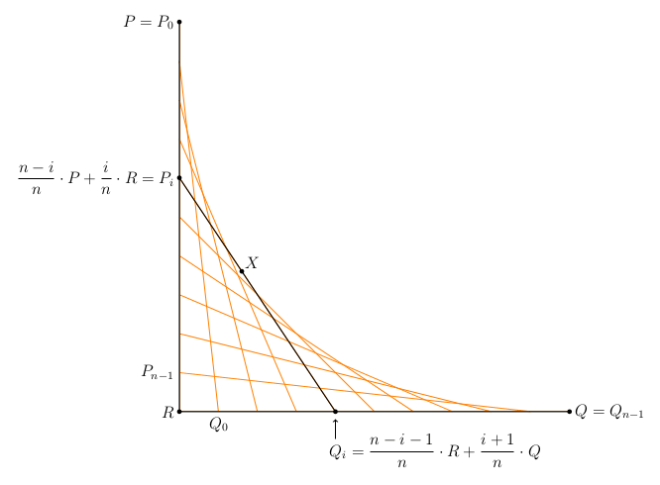

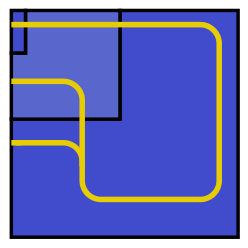

Thomas asked if it might be possible to keep the overall shape of the snowflake, but change the details at the edges. To discuss this possibility, let’s recall the algorithm for producing the snowflake (although this algorithm produces only one-third of the snowflake, so that three copies must be put together for the final image):

Thomas asked if it might be possible to keep the overall shape of the snowflake, but change the details at the edges. To discuss this possibility, let’s recall the algorithm for producing the snowflake (although this algorithm produces only one-third of the snowflake, so that three copies must be put together for the final image):

Amazing, isn’t it? Such a small change results in a very different feel to the final image. And of course once smaller changes are made, there’s no reason to stop. Maybe branch into more than two fractal routines? Or maybe perform sf1 when n is odd, and sf2 when n is even. Or….

Amazing, isn’t it? Such a small change results in a very different feel to the final image. And of course once smaller changes are made, there’s no reason to stop. Maybe branch into more than two fractal routines? Or maybe perform sf1 when n is odd, and sf2 when n is even. Or….

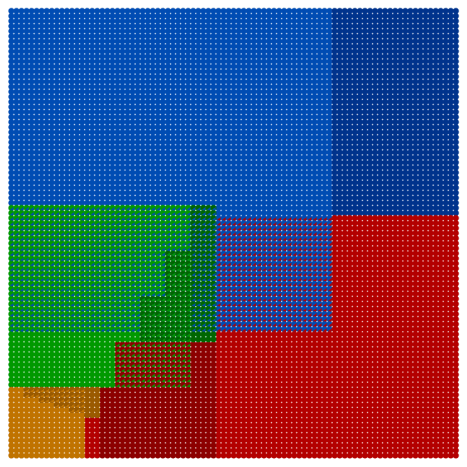

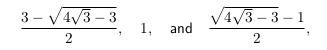

and these are some of the easier calculations! I won’t say more about that here — but you can read all about this dissection and many others in Greg’s book.

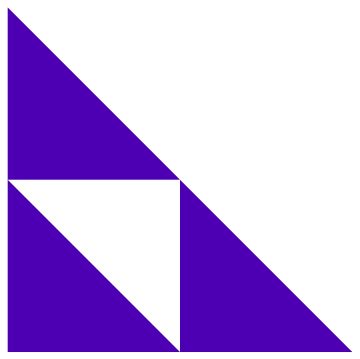

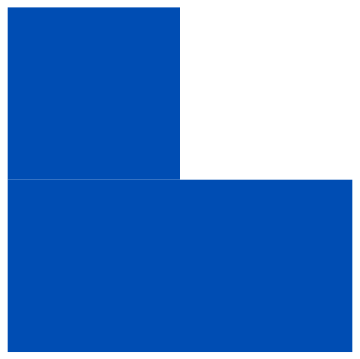

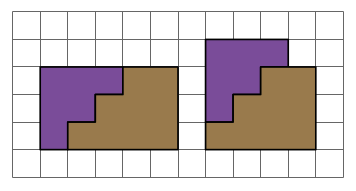

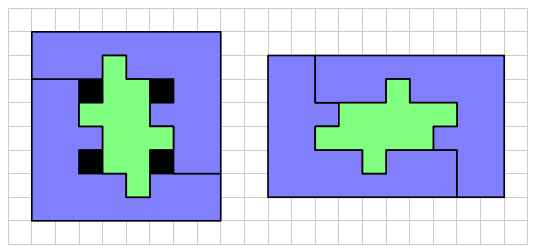

and these are some of the easier calculations! I won’t say more about that here — but you can read all about this dissection and many others in Greg’s book. This seems like an easy puzzle to solve, as shown below.

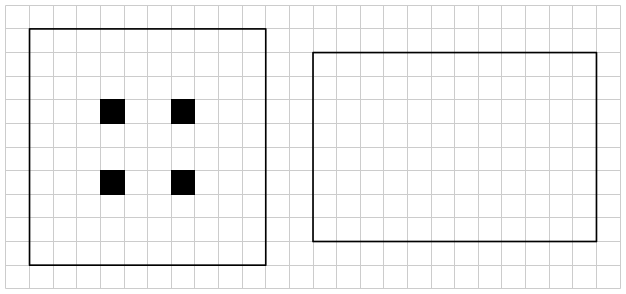

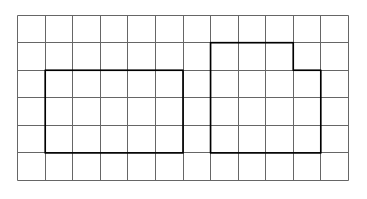

This seems like an easy puzzle to solve, as shown below. So yes, only two pieces are necessary — but one had to be rotated. Here is the question: can this puzzle be solved with just two pieces, but with neither piece rotated?

So yes, only two pieces are necessary — but one had to be rotated. Here is the question: can this puzzle be solved with just two pieces, but with neither piece rotated? This is a solution technique commonly used in Dissections Plane & Fancy. Why bother? In the world of geometric dissections (and it is a growing universe, surely, as any internet search will show), finding a minimum number of pieces is the primary objective. But of all solutions with this minimum number of pieces, “nicer” solutions require rotating the fewest number of pieces. And rotating none at all is — in an aesthetic sense — “best.” It is also preferable not to turn pieces over, although sometimes this cannot be avoided for minimal solutions.

This is a solution technique commonly used in Dissections Plane & Fancy. Why bother? In the world of geometric dissections (and it is a growing universe, surely, as any internet search will show), finding a minimum number of pieces is the primary objective. But of all solutions with this minimum number of pieces, “nicer” solutions require rotating the fewest number of pieces. And rotating none at all is — in an aesthetic sense — “best.” It is also preferable not to turn pieces over, although sometimes this cannot be avoided for minimal solutions. It is important to note that the octagons here are not regular. A quick glance through Dissections Plane & Fancy will reveal that dissections involving regular polygons are generally rather difficult (as the initial triangle-to-square example amply shows).

It is important to note that the octagons here are not regular. A quick glance through Dissections Plane & Fancy will reveal that dissections involving regular polygons are generally rather difficult (as the initial triangle-to-square example amply shows).

I’ll leave you with two puzzles to think about. Of course, you can just make up your own. If you come with anything interesting, feel free to comment!

I’ll leave you with two puzzles to think about. Of course, you can just make up your own. If you come with anything interesting, feel free to comment!