In this installment of Beguiling Games, we’ll learn how to play Splotch!

But first, I’ll start off by giving you the solution to the last puzzle I presented in the last installment. The statement of the puzzle is too long to repeat, so you can refresh your memory at Beguiling Games II.

First, it is important to note that Lucas’s statement actually provides no information! Suppose Ophelia’s card was Truthteller. Then she would have told the truth in Round 1, passed her card to Lucas, and he would truthfully have stated that she told the truth in Round 1.

But what if Ophelia’s card was Liar? Then her statement “I am a Truthteller” in Round 1 would in fact have been a lie. Now she passes her card to Lucas. He lies and says she told the truth in Round 1! What this means is Lucas could have made his statement in Round 2 regardless of what card Ophelia passed him.

Note that the same logic applies to Mordecai’s statement. He could have said “Lucas also told the truth in the first round” regardless of whether Lucas passed him a Truthteller or a Liar card.

Now let’s examine Nancy’s statement in some detail. She said that there is at least one liar at the table. Could she have lied?

Well, if the fact that the there is at least one liar at the table is false, that means everyone is a Truthteller. But there is no way Nancy could have known this, since the only two cards she saw were hers and the card passed to her by Mordecai.

That means Nancy must have told the truth in Round 2, and Mordecai must have passed her a Truthteller card. But in order for her to have sufficient information to say there is at least one Liar at the table, she must have been holding a Liar card in Round 1.

Now this information could be deduced by anyone at the table. In other words, anyone would know that Nancy held a Liar card in Round 1, and Mordecai held a Truthteller card. That leaves Lucas’s and Ophelia’s cards in Round 1.

The only person who could know both these cards would be Lucas — he knew his own card in Round 1, and he knew Ophelia’s card because she passed it to him in Round 2. So he had enough information to declare after Nancy’s statement.

It is important to point out that there is no way to know what Lucas’s and Ophelia’s cards actually were. All we need to know is that Lucas knew what both of them were.

Did you figure it out? It takes a little bit of reasoning, but all the facts were there.

Now as I mentioned in the last installment, this time I’d give you a geometrical two-player game to work out. I call it Splotch!

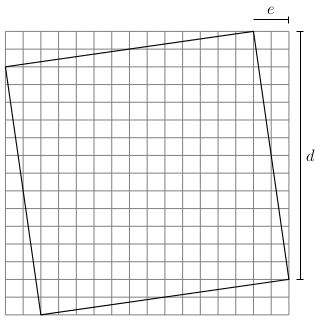

In the game of Splotch!, players alternate coloring in squares on a 4 x 4 grid. The goal is to create a target shape, called a splotch. A player wins when he or she colors in a square which completes a splotch, and then announces the win.

So if a player completes a splotch but doesn’t notice it and doesn’t announce the win, then play continues until someone completes another splotch. You can only call Splotch! on your turn, so you cannot win by calling it if your opponent fails to. It is also important to remember that the square you color in on your turn must be part of a splotch you announce.

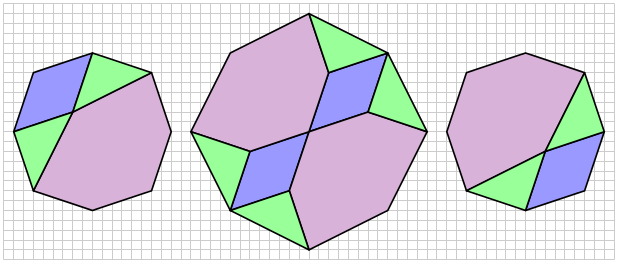

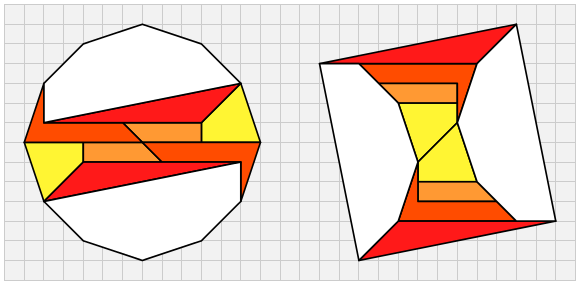

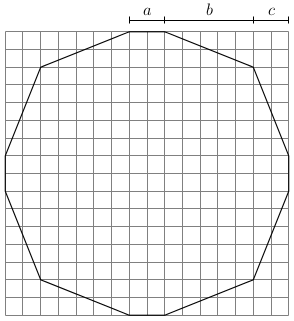

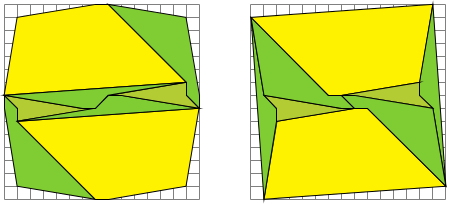

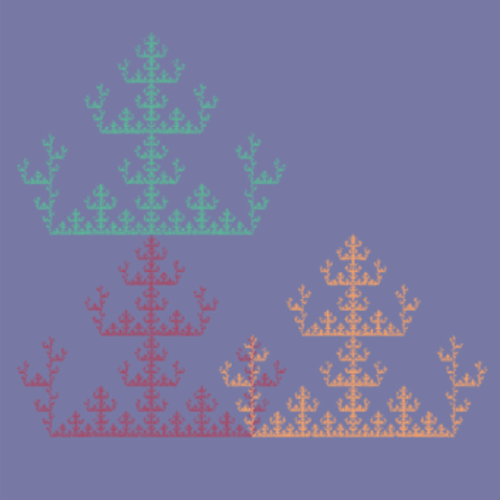

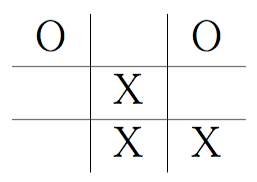

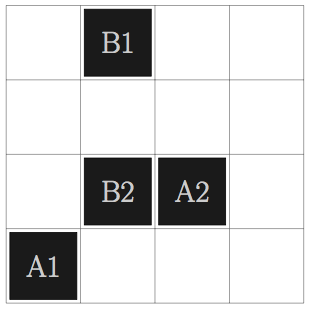

In the version of Splotch! I’m sharing with you this week, the target splotch is:

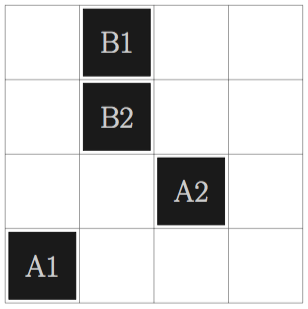

Just so you know how it works, let’s look at a sample game, shown below.

There are two players, A and B. A goes first, and plays in the lower left corner (labelled with A1). B colors in a square in the top row (B1). Then A’s second move is in the second row. B wins on the next play by completing — and announcing! — a splotch. The splotch may be rotated (as in this example), reflected, or even both! So you’ve got to watch carefully.

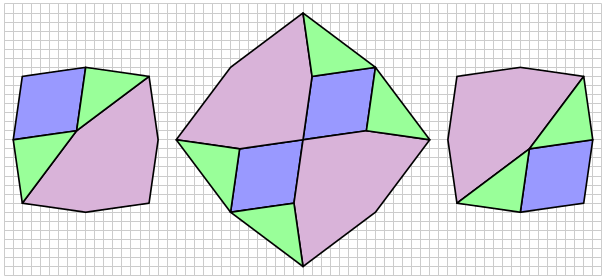

Now admittedly, A was not a very clever player in this round of Splotch! In fact, B could also have won by playing as follows:

But here is the question: In this version of Splotch!, which player can force a win every time? Remember: you must be able to provide a response to every move by your opponent! I’ll reveal which player can force a win in my next installment of Beguiling Games, and I’ll share my particular strategy for winning.

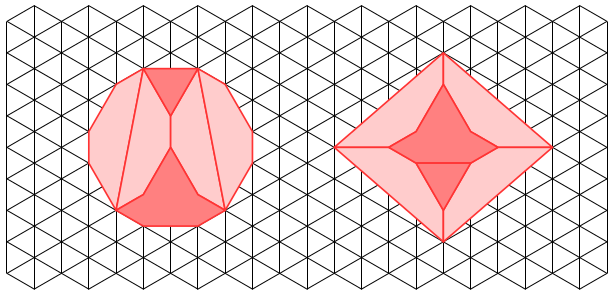

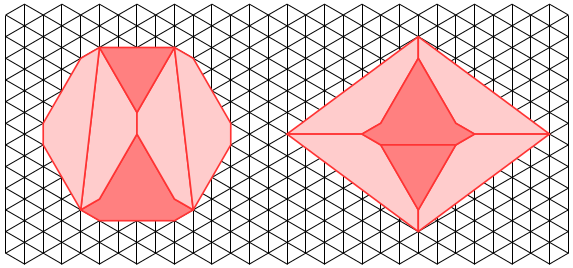

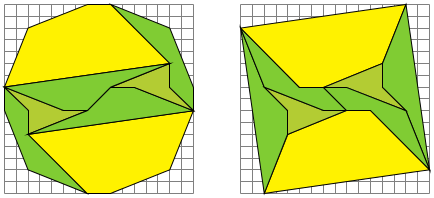

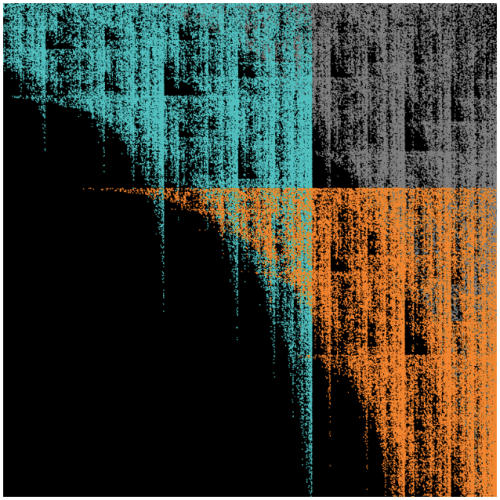

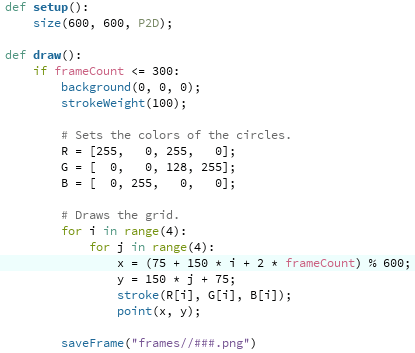

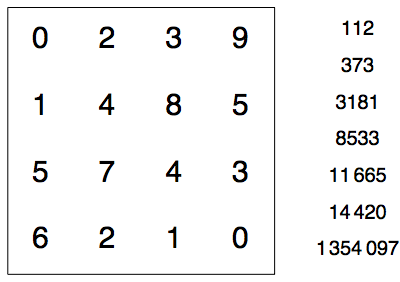

One final remark — a bit of a tangent, but related to puzzles and games. If you’ve been following my blog for a long while, you might remember my (fiendishly diabolical) number searches. (These were posted well over a year ago.)

Here, the numbers in the right are in base 10, but you have to convert them to another base to find them in the grid! You can read more about these puzzles here and here.

I submitted these puzzles to MAA Focus, the newsmagazine of the Mathematical Association of America. I am happy to report that they will be featured on the Puzzle Page in the December 2017/January 2018 issue!

Now I will admit that this doesn’t exactly make me famous, given the number of people who subscribe to MAA Focus. But I composed these puzzles specifically for my blog — so if I hadn’t decided to write a blog, these puzzles might never have been created. Perhaps another reason to write a blog!

Stay tuned for the next round of Beguiling Games, where you’ll learn (if you didn’t already figure it out for yourself) who has a winning strategy in the game of Splotch!