It’s hard to believe that the semester has finally come to an end! And I must say that Mathematics and Digital Art was one of most enjoyable courses I’ve ever taught. I’ll summarize my thoughts in a later reflective post, but today I’d like to showcase my students’ Final Projects. There really was some exceptional work — but I’ll let the images speak for themselves.

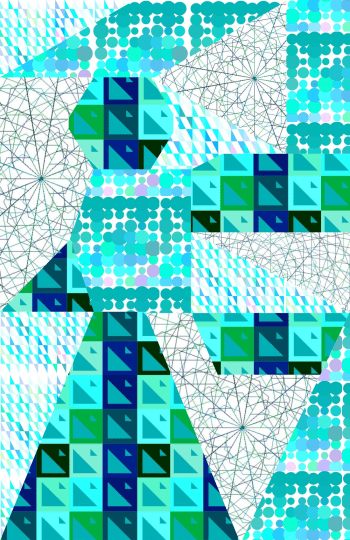

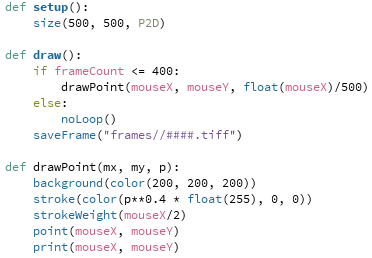

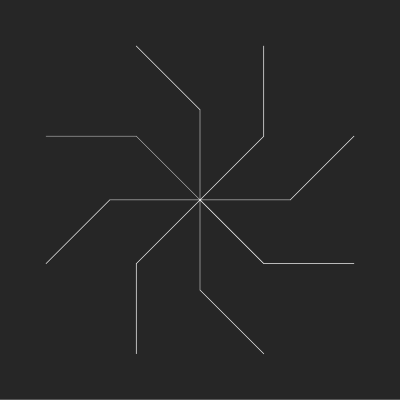

Many students built upon the work we did earlier in the semester. Safina used several different elements we explored during the course. In addition, she researched turtle graphics in Python to incorporate additional elements (those with lines emanating from a central point).

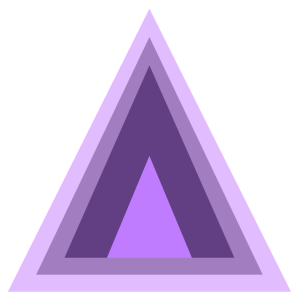

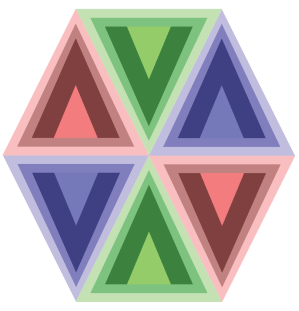

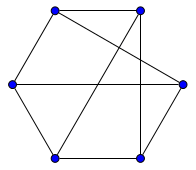

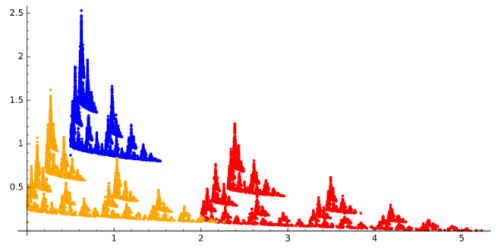

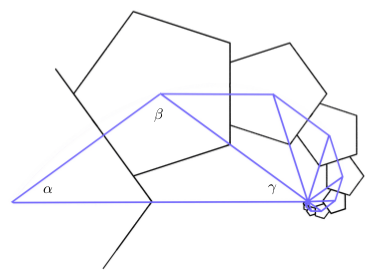

A few students especially enjoyed the work we did with color and Josef Albers, and created projects around different ways to contrast colors. Andrew created many variations on a triangular theme.

He took this idea further, and went so far as to combine different triangles in composite images.

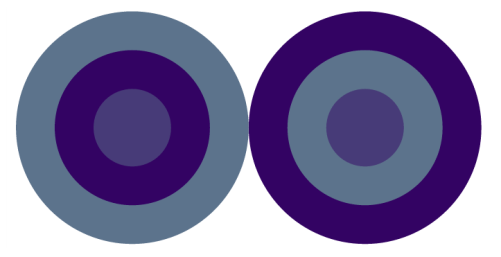

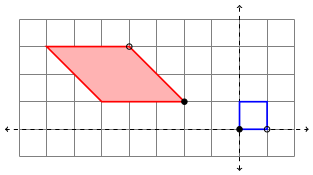

Julia, on the other hand, experimented with other geometrical objects. She played with having colors interact with each other, and created the following image. Although it may not look like it, the two center circles are in fact exactly the same color!

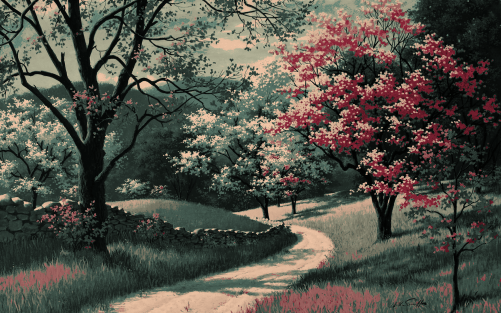

Two students were interested in image processing, and worked closely with Nick to learn how to use the appropriate Python libraries in order to work with uploaded images. Madison’s work focused on sampling pixels in an image and replacing them with larger circles to create an impressionistic effect. She found that using a gray background gave the best results.

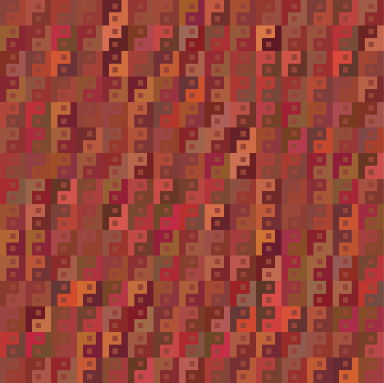

Lucas also worked with image processing. He began by choosing a fairly limited color palette. Then for each pixel in his image, he found the color on his palette “nearest” the color of that pixel (using the usual Euclidean distance on the RGB values), and then adjusted the brightness. The image below is one example illustrating this approach.

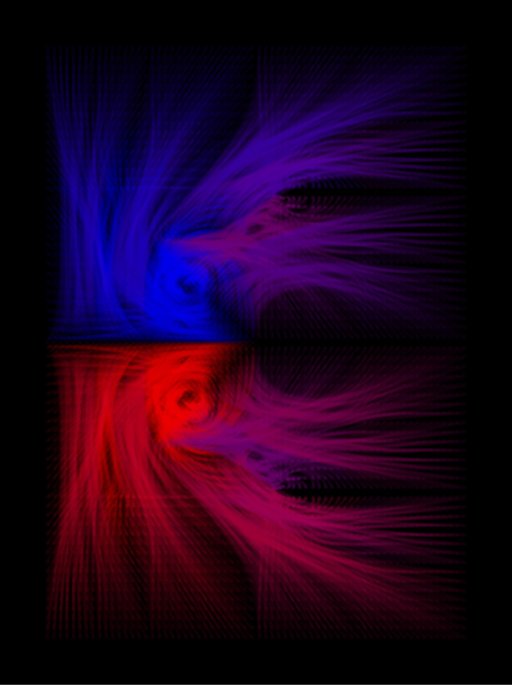

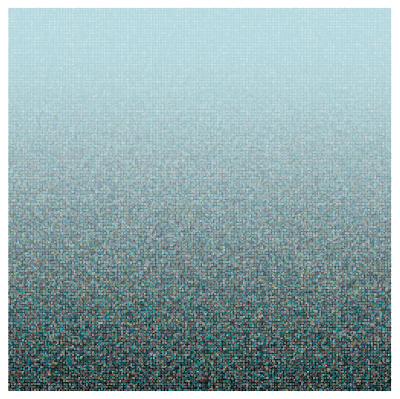

Two students worked with textures we experimented with earlier in the semester to create pieces like Evaporation. Maddie wanted to recreate a skyline of Dubai (photo from the Creative Commons).

She picked out particular elements to emphasize in her work. You can clearly see the tall buildings and lit windows in a screenshot of her movie.

Sharon was interested in working with some of Dali’s paintings, creating impressionistic images by mimicking Dali’s color palette. Here is her interpretation of The Elephants.

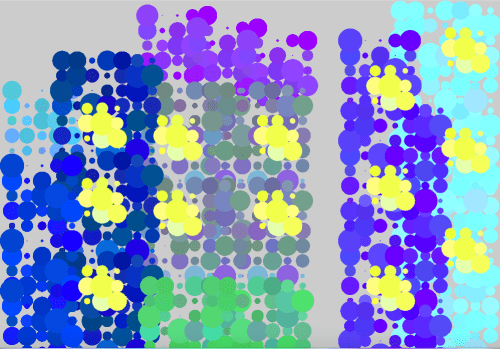

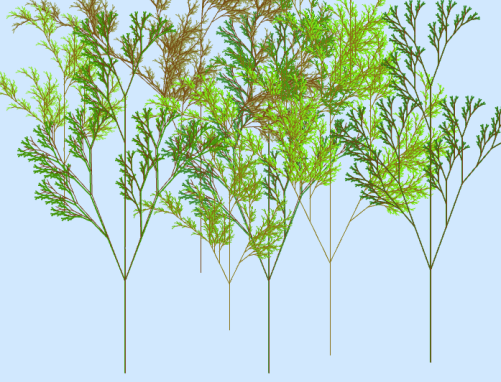

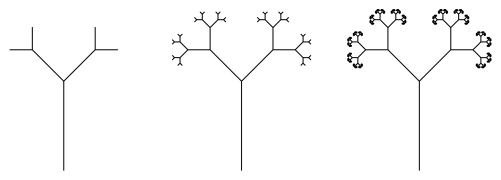

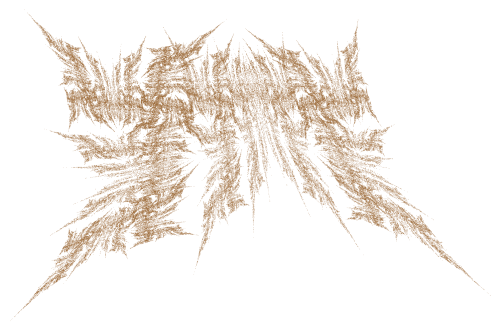

Although we only touched on L-systems briefly in class, Ella wanted to focus on them in her project. Nick also worked closely with her to create different effects. Here is a screenshot from one of her movies.

She was able to create some interesting effects by just slightly altering the parameters to L-systems which created trees and superimposing the new L-system on top of the original. This gave some depth to the trees in her forest.

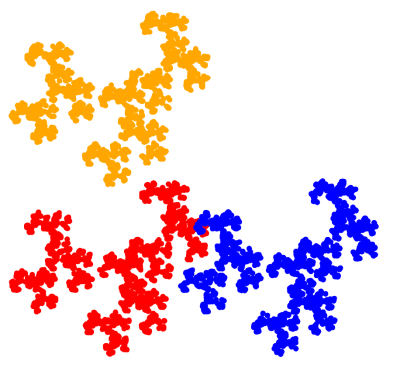

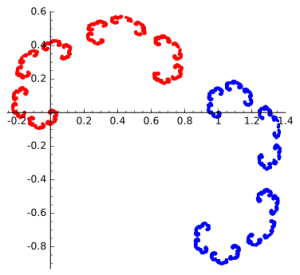

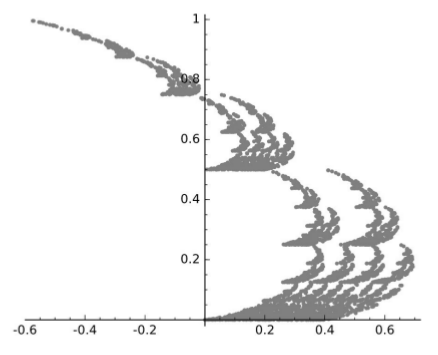

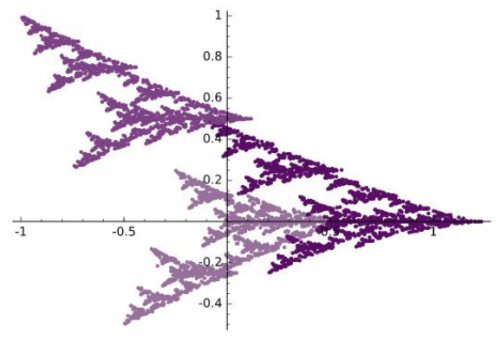

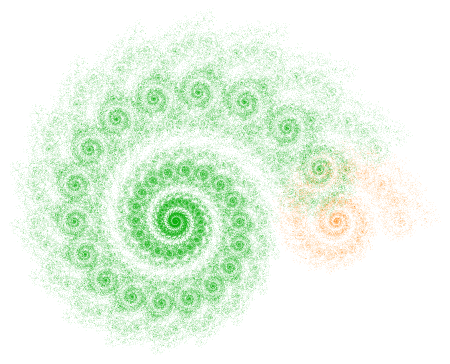

And one student decided to revisit Iterated Function Systems, but this time using nonlinear transformations in a variety of different ways. Here is one of her images.

So you can see the wide range of projects students undertook! This typically happens when you give students the freedom to choose their own direction. I was also inspired by the enthusiasm of some of the students’ presentations. They really got into their work.

The last assignment was to write a final Response Paper about the course. The prompt was the same as that for the Response Paper I assigned midway through the course, so I’m curious to see if their attitudes have changed. I’ll talk about what I learn in next week’s post!

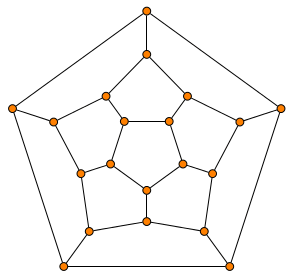

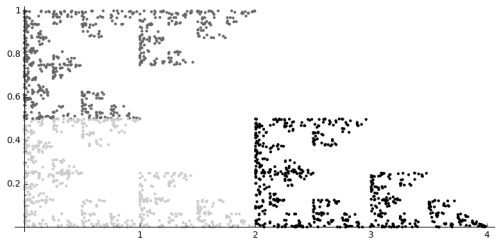

Figure 3: Logarithmic similar triangles

Figure 3: Logarithmic similar triangles